Neural Machine Translation with Monolingual Translation Memory

Hello fellow readers! In this post, I would like to share a recent advance in the field of Machine Translation. Specifically, I will be presenting the paper Neural Machine Translation with Monolingual Translation Memory by Cai et al, which received one of the six distinguished paper awards from ACL 2021.

Paper: https://aclanthology.org/2021.acl-long.567/ Code: https://github.com/jcyk/copyisallyouneed

So... what is Machine Translation?

You can probably guess from the name: over the last few decades, researchers have tried to get computers (a.k.a. machines) to translate between human languages. Their hard work has resulted in a plethora of products, like Google Translate and Microsoft Translator. I'm sure all of you have played with these tools before (if not, there's no time like the present) and have tried inputting various kinds of sentences. Their translation quality is quite impressive, and you can get near-native translations in many contexts (e.g. simple sentences between widely-spoken languages). However, you also may have noticed that some languages have better performance than others. This difference is due to the amount of usable translation data available (we'll go over what this means below). One of the key challenges being worked on today is to bridge this gap between low-resource and high-resource languages.

Data is Key

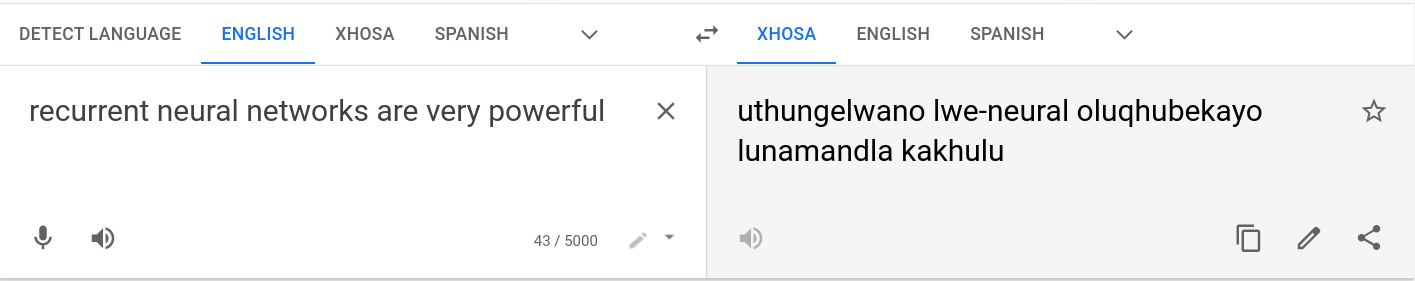

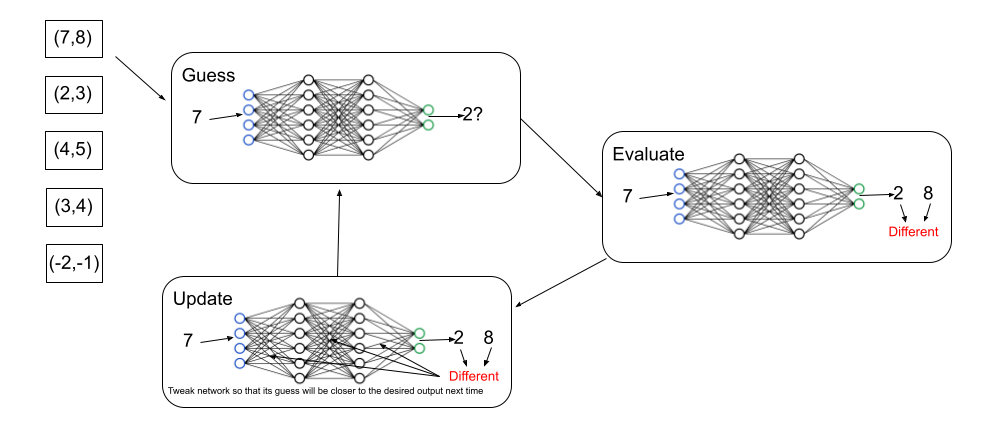

In order to understand what translation data is and why it is crucial for a good machine translation (MT) system, we first need to understand how these systems work. All of the current state-of-the-art use special kinds of programs called neural networks, which are infamous for being able to approximate any mathematical function by looking at examples.

If we can convert an English sentence into a list of numbers, and if we can do the same for a Spanish sentence, then in theory, it should be possible for the network to learn how to convert the numbers from one form into the other. And if we can train it on a large number of sentence pairs, it just might learn the grammatical rules well enough to provide good translations for unseen inputs.

Generally, hundreds-of-thousands or millions of parallel sentences are needed for good performance. However, it is hard to obtain pure, parallel datasets of this size for low-resource languages.

Monolingual Data

Even though low-resource languages like Xhosa may lack large amounts of parallel data, they still have vast amounts of untranslated text. If incorporated creatively, this monolingual (i.e. untranslated) text can also be used to help the network learn. Many strategies exist:

- Back-translation uses an okay-performing, reversed translation model to turn each sentence from the monolingual data into a synthetic (fake) parallel pair. We can then train the main model on this new parallel data to hopefully expose it to a wider variety of sentences.

- One could also use this data to pre-train the model before training on the parallel data. During the pre-training, all one has to do is delete random words from the monolingual corpus (e.g. a Xhosa book) and train the model to fill in the blanks. If the model does this task successfully and then trains on the parallel data, it may make better translations (at least, according to results published in Multilingual Denoising Pre-training for Neural Machine Translation).

However, the main advance I will be sharing with you presents an entirely new way of using monolingual data. Specifically, it combines monolingual data with a mechanism called Translation Memory.

Translation Memory

Before getting into what Translation Memory actually is, let me first motivate it a little. Intuitively, a good-performing translation program should be able to perform well in a wide variety of contexts. Specifically, it should be able to translate sentences from speeches, news articles, folk tales, research papers, tweets, random blog posts on machine translation, etc. However, if you want a generic, jack-of-all-trades model to make passable translations in all of these areas, you inevitably have to make some sacrifices. This is where the infrequent words problem comes in: words that are infrequently-encountered by the model during training get discarded as noise, reducing performance in specialized domains. For example, it could forget the word "chromosome" and translate a biology textbook incorrectly. This happens to humans too. If you're trying to become an expert at 10 topics in a short timespan, you may easily forget technical words crucial to each of the 10 topics. If one of those topics is the Medieval History of Mathematics, you may easily forget who al-Khawarizmi was, causing you to mis-attribute his discoveries. (It's even harder for a neural network, as it could never exploit the mnemonic connection between algorithm and al-Khawarizmi 😄).

However, the good news is that computers can look things up extremely quickly, far more quickly than humans. Imagine if you were tested on the Medieval History of Mathematics, but you had the textbook's glossary with you. All of a sudden, if you were asked about al-Khawarizmi, you could provide the correct answer in the time that it takes you to look him up. Translation Memory essentially imbues the neural network with this same capability.

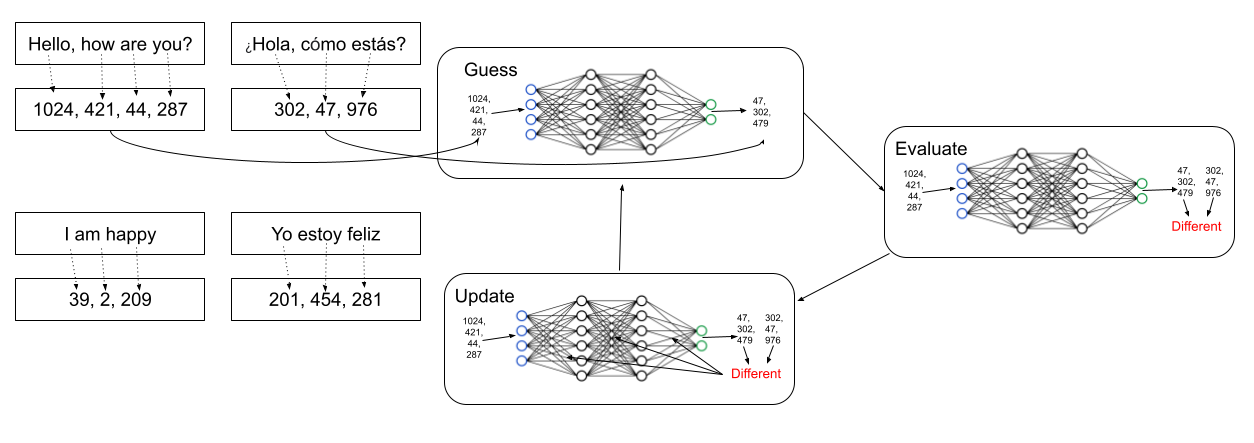

Essentially, each time the network is asked to generate a word, it can reference the translation memory (a bilingual dictionary mapping words between the source and target languages) to provide a more nuanced translation. The original researchers who proposed this concept came up with a two-component model architecture. One component consists of a neural network that generates its own "guess" for the translation word-by-word. The other component, called a memory component, retrieves the translations for each source word from a large dictionary. These two proposals are then combined, so that the one with higher confidence is used in the final translation.

(Note that everything in this section comes from Memory-augmented Neural Machine Translation [2]. If you want to learn more, go read their paper! I promise you, it's very interesting).

End of Intro

Thank you so much for bearing with me through the introduction. I did my best to put these topics into understandable words, but I may have accidentally glossed over something without explaining. If you have any questions or feedback, please don't hesitate to reach out to me at rajansaini@ucsb.edu.

Monolingual Translation Memory

Now, the moment we have all been waiting for has finally arrived. We can finally talk about what Monolingual Translation Memory is, how it exploits monolingual data, and what its implications are.

Intuition

The original Translation Memory introduced above is quite powerful, but it has a few limitations:

- The first is that it requires a parallel, bilingual dictionary. This means that when trying to come up with a translation for an unknown word, the model will try to translate it directly rather than use the entire sentence's context.

- In addition, it is impossible for the retrieval mechanism itself to adapt as the model trains (a dictionary cannot change, even though other words might be more relevant).

The new Monolingual Translation Memory is designed to solve both of these issues by:

- Using entire aligned sentences instead of a word-to-word dictionary. Such a sentence-sentence dictionary would be prohibitively long for humans to read through, but a clever retrieval mechanism would make it usable for a computer program. Furthermore, they use another neural network called a "parallel encoder" to determine whether two sentences are translations of each other. This allows them to associate monolingual sentences with existing translations, exploding the number of possibilities! (If you're confused by this, don't worry; this will be explained in more detail in a section below)

- Making the retrieval mechanism learnable. This means that as the model trains on a parallel corpus, the retrieval mechanism should also be able to adapt itself. Specifically, it should learn to provide the most relevant translations from a large set of sentences (including sentences outside the original sentence-sentence dictionary).

Parallel Encoders

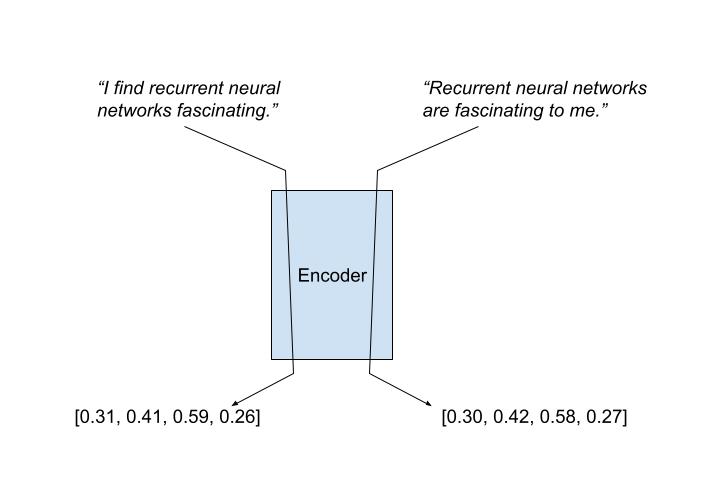

The main secret behind this advance is its usage of parallel encoders. These are neural networks (i.e. mathematical functions) that map sentences to their meaning. More precisely, they map sentence embeddings (the original sentence converted to numbers, see "Data is Key") to an encoding vector. The hope is for sentences with the same meaning to have the same encoding, even if they are expressed differently. For example, a good encoder would give "I find recurrent neural networks fascinating" and "recurrent neural networks are fascinating to me" similar encodings.

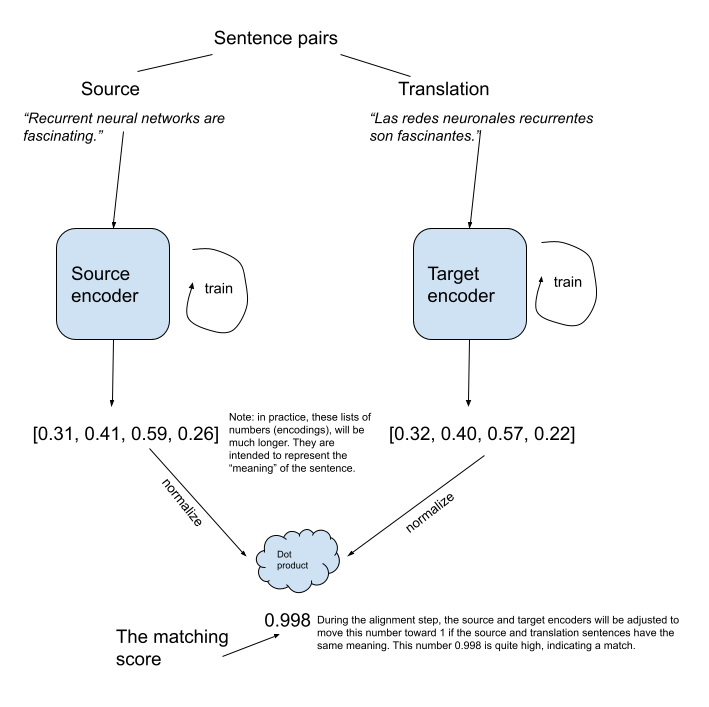

We can also extend this idea across languages! We can have an encoder for each language that converts their sentences into a shared "meaning space". More precisely, two sentences from different languages that share the same meaning should get mapped to similar encoding vectors:

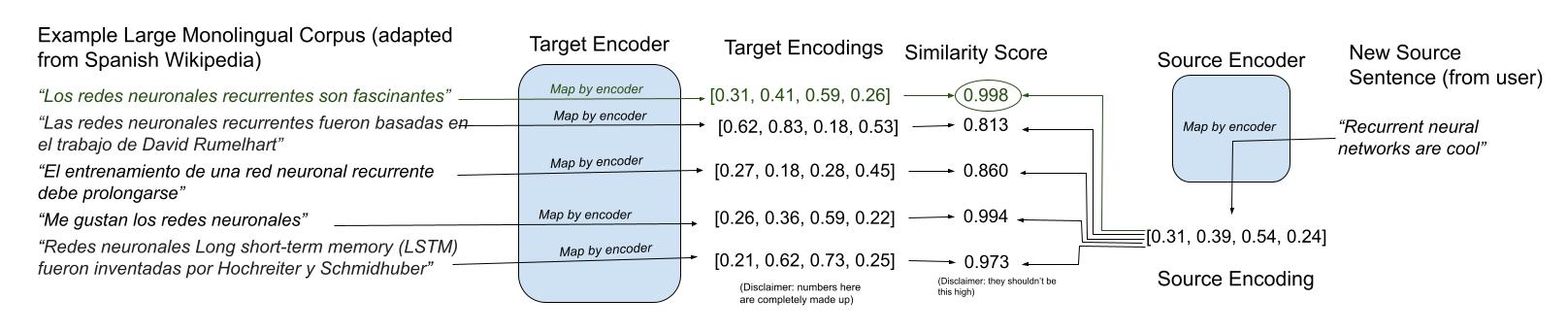

Before we train our main neural network, we first train the target and source encoders on parallel text. The goal is for them to output identical encodings when they have the same meaning and different encodings when their meaning is different. This is called the "alignment step". Then we can run the target encoder over a large untranslated corpus to encode each sentence. Then, every time the user wants a new sentence translated, we can find the target sentence with closest meaning by comparing the encodings:

Through this method, every sentence ever written in the target language can now be retrieved (at least in theory). The researchers that proposed this process found that searching for the most-similar encoding is equivalent to performing a Maximum Inner Product Search (MIPS). Fast algorithms that solve MIPS have already been discovered, so they can also be used for a speedy retrieval.

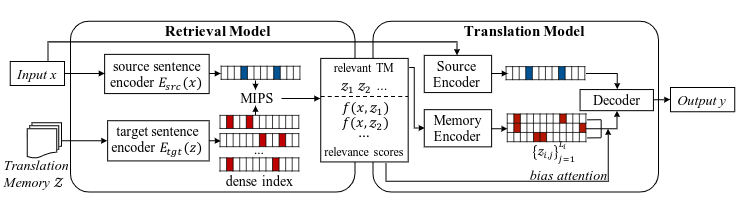

Main Translation Model

The retrieval model described above will give native translations, since it searches through text originally written by humans. However, what about completely new inputs for which direct translations have never existed? In that case, we would still want to use a larger neural network to create novel translations. If we could somehow allow that network to have access to some of the best-matched sentences found by the retrieval model, this should give us the best of both worlds. In highly domain-specific cases, the retrieval model could pull up relevant words or context that the network can use. The network could then produce a translation that matches the source sentence while taking advantage of these technical words.

In order to pass the encodings and retrieved sentences to the translation model, we can use a memory encoder and an attention mechanism. The memory encoder is a simple learnable matrix that maps each sentence to a new vector space (this section is a little more advanced, but "learnable" means that the matrix's weights will get adjusted during training) . I would guess that this is done so that the source sentence and retrieved sentences get mapped to the same vector space. This way, they can be meaningfully compared with and added to each other. After the retrieved sentences get transformed into memory embeddings, an attention mechanism combines them with the source sentences (scaled back by their confidences). I will not explain the full details behind how the attention mechanism works (this article has a great explanation), but the intuitive idea is that it highlights the relevant items from the memory encoder based on the source embeddings. After that, a decoder network converts the attention scores into the final translation, word-by-word.

Done! At last

Whew! That was a lot! Anyway, this is my possibly-confusing attempt at sharing one of the latest advances in Machine Translation. If you need any clarification (especially with the translation model above), definitely feel free to reach out! Otherwise, thank you so much for your patience to have made it this far.

References

[1] Deng Cai, Yan Wang, Huayang Li, Wai Lam, Lemao Liu. Neural Machine Translation with Monolingual Translation Memory. ACL 2021.

[2] Yang Feng, Shiyue Zhang, Andi Zhang, Dong Wang, Andrew Abel. Memory-augmented Neural Machine Translation. EMNLP 2017.

[3] Victor Zhou. “Neural Networks from Scratch.” Victor Zhou, Victor Zhou, 9 Feb. 2020, https://victorzhou.com/series/neural-networks-from-scratch/.