Learning Shared Semantic Space for Speech-to-Text Translation

How to develop a translation model that can take both speech and text as input and translate to target language? Can we borrow inspiration from human brain study to improve the speech translation models?

Reading Time: About 15 minutes.

Paper:https://arxiv.org/pdf/2105.03095.pdf

Github: https://github.com/Glaciohound/Chimera-ST

Introduction

Although it seems difficult for normal people to acquire more than two languages, according to the Wikipedia there are many polyglots who can speak tens of languages. For example, Ziad Fazah, speaking a total of 59 world languages, is believed to be the world’s greatest living polyglot. However, compared with others in the history his record does not stand out. It was recorded that Cardinal Giuseppe Caspar Mezzofanti, who was born in 1774, could speak 38 languages and 40 dialects. Meanwhile, the 10th-century Muslim polymath Al-Farabi was claimed to know 70 languages. The German Hans Conon von der Gabelentz, born in 1807, researched and published books about grammars for 80 languages. The highest record probably belongs to Sir John Bowring, Governor of Hong Kong from 1854 to 1859, who was said to know 200 languages, and capable of speaking 100. But it turns out extremely difficult for machine to learn natural languages like humans, in particular, despite its huge potential applications, speech translation has always been a challenge for machine. One common advantage is that those polyglots all benefit from not only text, but also audio corpus. However, how to utilize both audio and text information to help machine speech translation has not been fully exploited. The challenge comes from the intrinsic difference of modality between audio and text.

A recent work Chimera from ByteDance AI Lab and UIUC aims to draw strengths from both modalities for speech translation [1]. Their key idea is to represent text and audio inputs differently, then fuse them together by projecting audio and text features into a common semantic representation to boost the ST performance.

There are two main advantages for including audio and text data together for training one ST model. First, humans learn languages simultaneously from audio, text and videos rather than pure text. Inspired by this observation, it is believed that text knowledge can provide additional insights for ST. Second, since MT corpus is much larger compared with small corpus of ST, which is also expensive to create, incorporating MT text provides much fruitful training data and is expected to yield improvements on ST when bridging the modality gap properly.

Taking those benefits into consideration, the Chimera model showed significant improvements by unifying MT and ST tasks on the benchmark ST datasets containing more than ten languages pairs.

Unlike previous translation models, Chimera has established a successful paradigm of bridging the modality gap between text and audio for speech translation. This is similar to multi-modality MT, in which images can improve the text translation quality. Considering the pixel level information in images is accurately described, the audio is even noisier and leads to more challenges.

Chimera is designed for an end-to-end speech-to-text translation task. It has two advantages. First, the translation quality can be consistently improved by leveraging a large amount of external machine translation data. In rich-resource directions, such as the largest speech translation dataset MuST-C, which already contains translations from English to eight languages with each pair consisting of at least 385 hours of audio recordings, Chimera can still significantly improve the quality, reaching a new State-Of-The-Art(SOTA) BLEU score on all language pairs. In low-resource directions, such as LibriSpeech dataset containing only 100 hours of training data, Chimera also performs surprisingly well and consistently outperforms the previous best results. Finally, they verified the common knowledge conveyed between these audio and text tasks indeed comes from the shared semantic space and thus paves a new way for augmenting training resources across modalities.

Chimera can be thought of as a multimodal in the field of speech translation in general. When you need to develop a speech translation model but don't have enough audio data, you may consider using Chimera, and it can turn out to be better than your expectation! The research data, codes and resources are also kindly published by the authors.

Next, we will introduce and analyze Chimera from three aspects: 1) the challenges of bridging the gap between audio and text for speech translation; 2) the motivation and methods of Chimera; 3) the performance and analysis of Chimera.

Challenges in speech translation

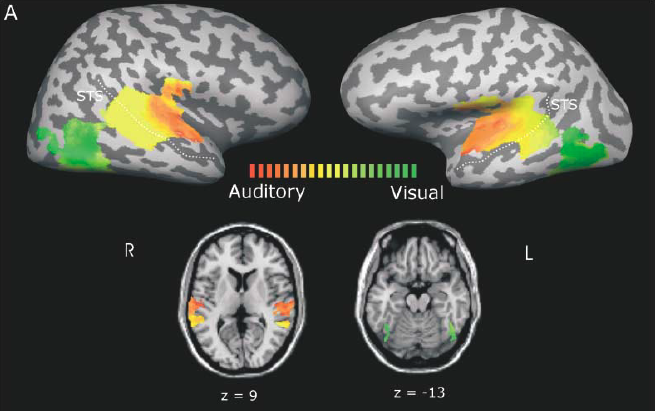

The current paradigm of artificial intelligence highly depends on training on a large dataset, and thus make predictions on a small test set. However, different modalities of data have been labeled for various tasks but seldom been utilized together due to the modality gap of data representations. For example, billions of parallel MT corpora have been ignored as additional training data for SP for a long time. At the meanwhile, the data of ST is always in the dearth due to the difficulty of collection and high cost. Looking at the relatively smaller amount of parallel data for ST compared with MT, it is natural to have the idea of combining them together. Unfortunately, although they both encode human languages, they are dissimilar in both coding attributes(pitch, volume, and intonation versus words, suffixes, and punctuation) and length(thousands of time frames versus tens of words). Therefore, it has always been a challenge to unify representations from audio and text. The recent evidence from functional neuroimaging identifies certain regions in brain that the processing stream for speech sounds and visual text correlates positively with the subjects' reading ability. This finding provides the intuition for developing a multi-modality converged representation of audio and text in language activities. But only little previous research explored this direction possibly due to the difficulties of modality fusion and marginal improvements. Surprisingly, Chimera establishes a new bridge to fill the modality gap between speech and text and can serve as a new foundation in this area.

In the above figure[2], the color represents relative contribution of unimodal visual (green), unimodal auditory (red), and similar contribution of visual and auditory predictors (yellow) to explaining signal variance. The lateral and inferior occipital-temporal cortex were active by unimodal presentation of letters, while Heschl's gyrus (primary auditory cortex) and portions of the superotemporal cortex were activated by unimodal presentation of speech sounds. This neuroimaging evidence convinces the connection of audio and text in human brain, serving as theoretical foundation of modality fusion.

Motivation and Techniques of Chimera

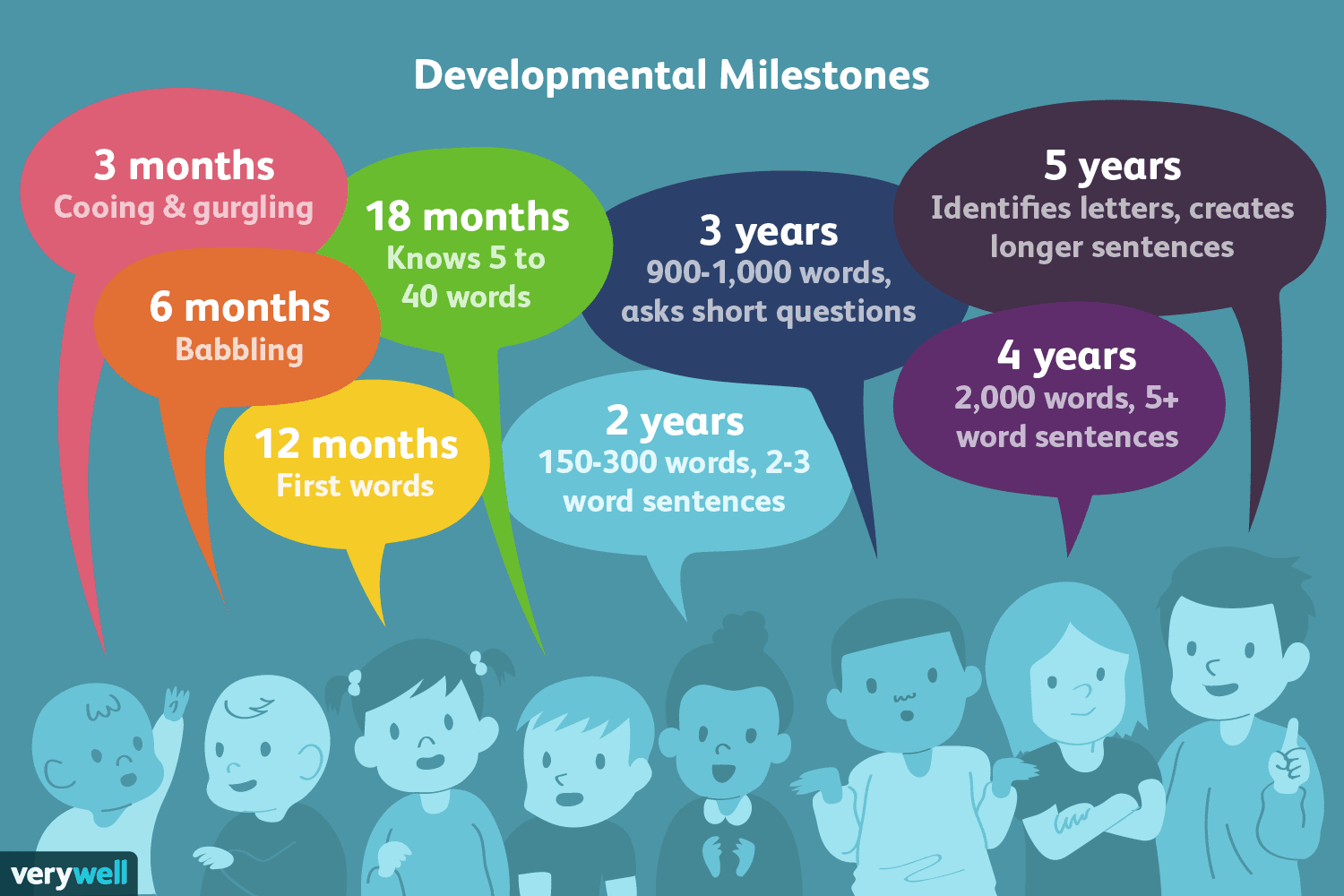

For language learners, a very interesting phenomenon is that they learn better by audio and text together rather than text only. The aforementioned famous polyglots also stated that their success originated from various interactions with native speakers in other languages, such as listening, reading, and speaking. Nowadays, many people also learn new languages by watching movies, in which they will be immersed in audio and subtitles. In particular, the above figure is Ioannis Ikonomou, who was born in Greek and now works as translator for European Union. Ikonomou can speak 32 languages and could also translate those languages to each other in daily work. According to his interview, he was born in a famous tourism city, where people from all over tha world visit there every day. Under the influence of different tourists, he learned English at 5 years old, German at 7 years old, Italian at 10 years old, Russian at 13 years old, East African Swahili at the age of 14, and Turkish at the age of 16. He said "Learning Polish can make Polish dumplings better. Learning Russian is to understand Dostoyevsky, Persian is to appreciate ancient Persian poetry, and Hungarian is to understand Hungarian folk songs. For German, it is to understand the veteran show "Mirror of the World" every Sunday evening."[3]. It is worthy to point that he learned most languages when he was still a child, demonstrating strong language ability of human children.

The above figure shows the developmental milestones of human children learners. Children first learns how to speak from their family and thus how to speak fluently, read and write formally at school.

All those evidence demonstrates that combining audio and text could help humans learn a new language. A natural next step is to apply this idea in speech machine translation.

The design goal of Chimera is based on such considerations: design a general framework to learn the combination of audio and text from languages, and then it will benefit from this combined pre-training when migrating to the new speech translation direction. Just like language learners, after learning two modalities, the one modality becomes easier. The design of Chimera follows three basic principles: first, learn the shared semantic memory module to bridge the gap between the representation of audio and text; Second, the training objective of pre-training comes from three parts: 1) the speech-to-text translation training, 2) the text machine translation training, and 3) Bi-modal contrastive training; Third, train on external MT corpora and then apply the model in ST task.

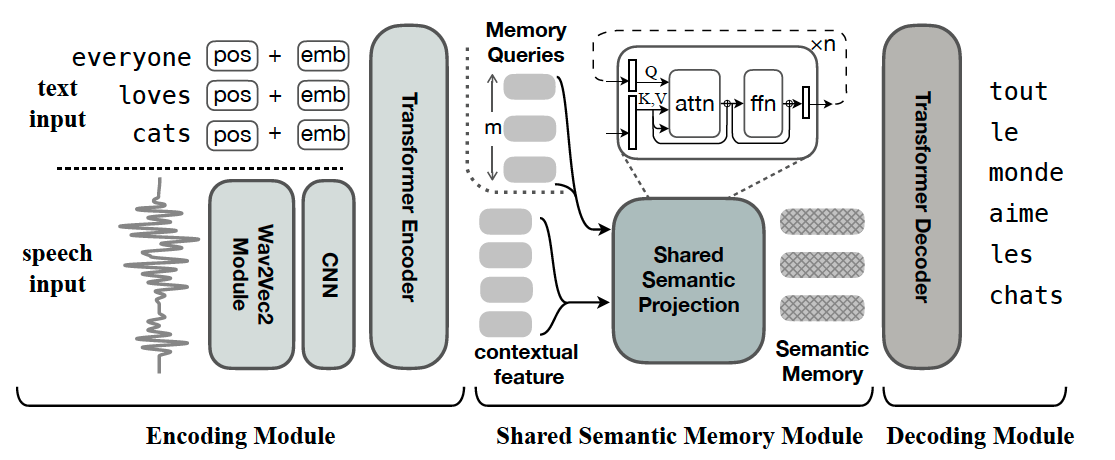

Shared semantic memory

Chimera follows a transformer based encoder-decoder framework and above is an overview. Word embedding for text input and the Wav2vec2[4] sub-module for speech input are both included in the Encoder Module. The shared semantic projection Module generates semantic memory with fixed-size representation from contextual features using its memory query. The Decoder Module decodes semantic memory translation.

Chimera follows a transformer based encoder-decoder framework and above is an overview. Word embedding for text input and the Wav2vec2[4] sub-module for speech input are both included in the Encoder Module. The shared semantic projection Module generates semantic memory with fixed-size representation from contextual features using its memory query. The Decoder Module decodes semantic memory translation.

Since the encoder and decoder are actually standard modules based on transformer[5], which have been proven to be the SOTA design in many natural language processing tasks, the shared semantic memory module is the key to success of Chimera. So here we will mainly discuss the fantastic design of this shared module. Among this framework, the module relies heavily on shared semantic projection. In fact, contextual elements of speech and text can have a wide range of distributions and lengths. The shared semantic projection should, in theory, compute a fixed number of semantic features as output semantic memories. This module takes the contextual information extracted from the encoding module as input and outputs semantic memories with a set length of m. It is made up of n layers of attention. It stores a tuple of m trainable input-dependent memory queries as the initial "memories" to represent the categories of required semantic information. Attention "keys" and "values" are provided by unimodal contextual features, but attention "queries" are provided by memories. Memories are fed into the n shared semantic projection layers in an iterative fashion, with each layer's output being used as input to the next layer. The semantic memory is created from the final output.

Dataset and preprocessing

Two datasets were used for conducting experiments to verify the effectiveness of Chimera. One is called MuST-C, the largest ST corpus, which contains translations from English(EN) to 8 languages: Dutch (NL), French (FR), German (DE), Italian (IT), Portuguese (PT), Romanian(RO), Russian (RU), and Spanish (ES). With each pair consisting of at least 385 hours of audio recordings. Another popular one is Augmented LibriSpeech Dataset (En-Fr), which is composed of aligned e-books in French and their human reading in English of 100 hours. They also incorporate data from WMT, OpenSubtitles and OPUS100 translation tasks as pretraining corpora.

In practice, speech input, the 16-bit raw wave sequences are normalized by a factor of 215 to the range of [-1, 1), which uses the Wav2Vec2 Module following the base configuration in [4]. The shared Transformer encoder consists of 6 layers. The memory queries are 64 512- dimensional vectors. The parameters of shared semantic projection resemble a 3-layer Transformer encoder. The Transformer decoder has 6 layers. Each of these Transformer layers, except for those in the Wav2Vec2 module, has an embedding dimension of 512, a hidden dimension of 512, and 8 attention heads.

Chimera contains around 165M parameters. The whole training process for one trial on 8 Nvidia Tesla-V100 GPUs generally takes 20 –40 hours according to the translation direction.

Effectiveness of Chimera

In summary, Chimera has the following advantages:

- New state-of-the-art performance on all language pairs

Even though they did not use Google Translate results on Augmented Librispeech as most baselines, Chimera obtains state-of-the-art performance on all language pairs. Chimera's EN-DE results use WMT14+OpenSubtitles for MT pretraining, whereas the original paper also contains a full ablation research on the effect of MT data. It's worth noting that the improvement in EN-PT isn't as dramatic as it is in EN-DE and EN-FR. This is due to a mismatch in data between OPUS100 and MuST-C. OPUS100 has a high amount of sentences from movie subtitles, which are more informal, feature repeated lines, and address issues that are not covered in MuST-C public speeches.

- Successfully share knowledge across tasks

Additional trial findings corroborate their design of auxiliary tasks by demonstrating its ability to acquire a well-structured shared semantic space as well as successfully exchange learned knowledge between MT and ST.

Here are some representative experimental results:

1. Benchmark Experiments

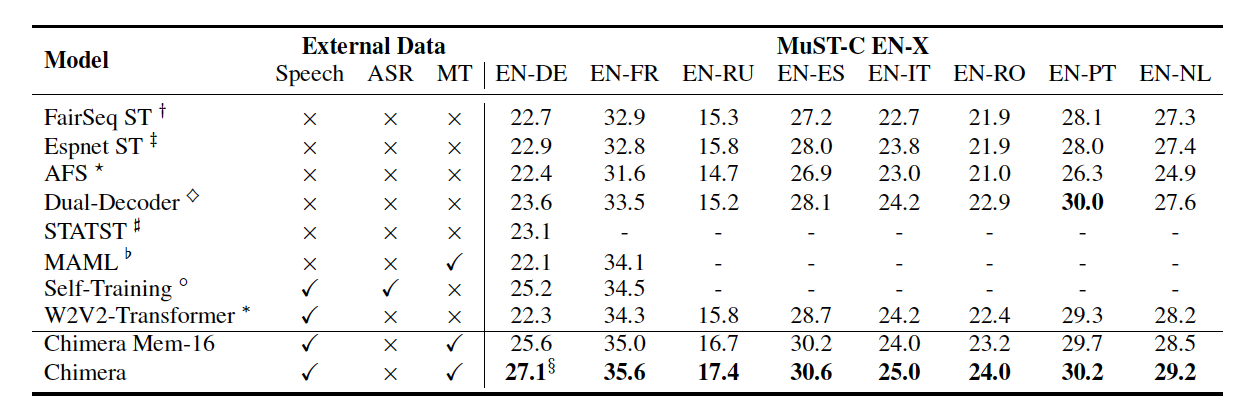

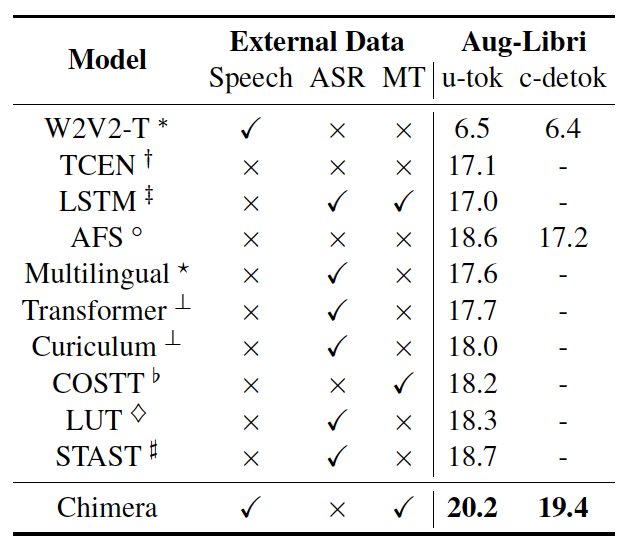

The below two tables demonstrate the main results on tst-COMMON subset on all 8 languages in MuST-C dataset amd on LibriSpeech English-French dataset.

Table 1: Main results on tst-COMMON subset on all 8 languages in MuST-C dataset.

Table 2: Results on LibriSpeech English-French dataset.

2. Visualizations

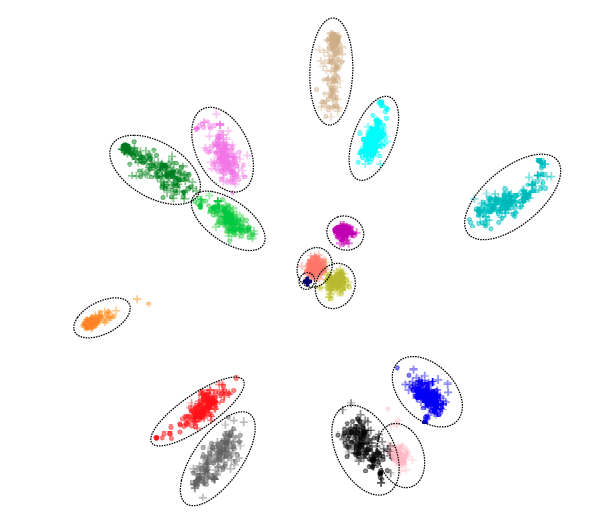

Regardless of the input modality, the shared semantic projection is designed to extract only the semantic categories of information required for decoding. To validate this hypothesis, a 2-dimensional PCA projection was performed in the semantic memories across different samples.

In the above figure, each colored cluster (circled out) represents a semantic memory element. A '.' corresponds to a speech semantic memory, and a “+” marks a text one. It is obvious that semantic memories are strongly clustered, with each individual learning a specific region. The model's capacity to overlook representation disparities and bridge the modality gap is demonstrated by the close distance of speech and text representations inside the same region.

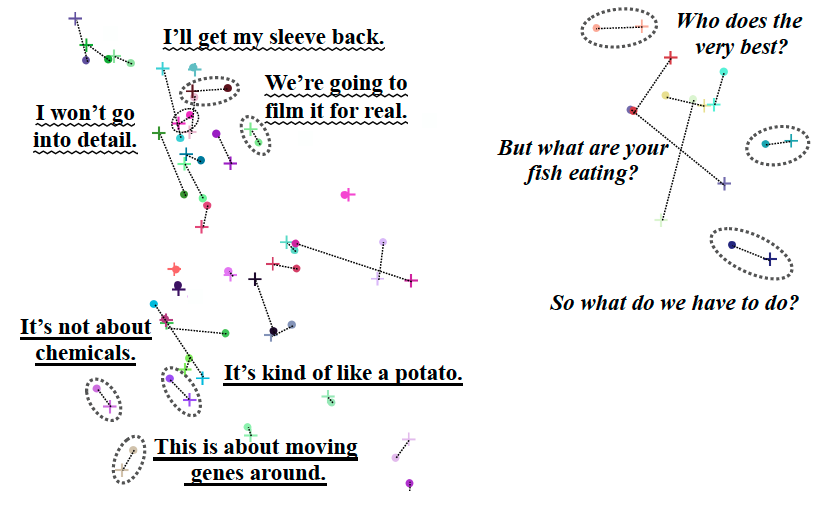

One randomly selected semantic memory subspace was analyzed by PCA to its related cluster to get a better look at the structure of each semantic memory subspace.

The above figure is the visualization of one specific semantic memory with no different samples or modalities. "+" denotes text representations, while "." denotes speech representations. Marks of the same color are linked by dashed lines and come from the same speech-transcript pair. Some speech-transcript pairs have been circled and their transcripts have been annotated. Three different fonts denote three different sets of transcripts with similar patterns. As can be seen from the circles, the matched speech and transcript inputs are indeed close to each other. Such results provide strong evidence of the efficacy of the semantic memory module, especially when considering audio and text represent different modalities.

Summary

Going back to the polyglots, who successfully learn new languages through various kinds of interactions with the environments such as speaking, reading and writing, Chimera makes one important step towards drawing strength from text machine translation to advance speech translation. In general, Chimera unites MT and ST tasks by projecting audio and text data to a shared semantic representation, boosting performance on ST benchmarks MuST-C and Augmented Librispeech to a new state-of-the-art. Further visualizations show that the shared semantic space does indeed convey common knowledge between these two tasks, paving the path for novel ways to supplement training materials across modalities.

In the future, we are looking forward to more advanced techniques to solve two additional problems: 1) how to tightly align speech and text representations and 2) how to make the workflows of MT and ST fully shared. Since ST is an exciting new area, there are a lot of interesting research and progress almost every week. In the near future, we believe a beautiful new world, where the real time speech translation comes true and the language barriers among countries and nations are broken, is waiting fo us.

References

[1] Han, Chi, Mingxuan Wang, Heng Ji, and Lei Li. "Learning Shared Semantic Space for Speech-to-Text Translation." ACL 2021.

[2] Van Atteveldt, Nienke, Elia Formisano, Rainer Goebel, and Leo Blomert. "Integration of letters and speech sounds in the human brain." Neuron 43, no. 2 (2004): 271-282.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ioannis_Ikonomou

[4] Alexei Baevski, Yuhao Zhou, Abdelrahman Mohamed, and Michael Auli. 2020. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 33, pages 12449–12460. Curran Associates, Inc.

[5] Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. "Attention is all you need." In Advances in neural information processing systems, pp. 5998-6008. 2017.